If I had to describe the scent of my childhood, it would be a mix of Keo-Karpin hair oil, sandalwood soap, sharp wafts of mustard oil, and the smoky edges of charred banana leaves. These weren’t just smells—they were markers of comfort. And they all belonged to one person: Amma, my paternal grandmother.

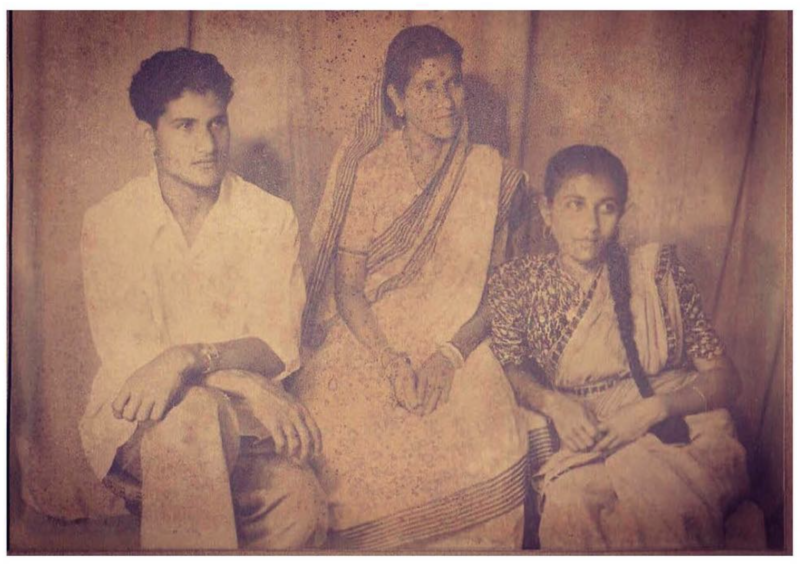

Priyanjali’s Amma on the extreme right, with her brother and elder sister. Photo courtesy Priyanjali Datta

Amma grew up in pre-Partition Borishal, now in Bangladesh. Her stories were full of narrations of waterways, coconut trees, and an almost mythical abundance—so much ilish that excess fish would sometimes be burnt. Orphaned at a young age, she left with her younger brother and crossed into what would soon be called India. She built a life in Agartala, then moved to Kolkata, raising three children and five grandchildren.

She’s no longer with us, but the world she created lingers—in habits, in language, and most vividly, in food.

I’m the third of her grandchildren, now living in Delhi for over 15 years. And like many from my generation, I often find myself looking back, trying to understand where I come from. Amma told us so much about her life, but we never saw the land that shaped her. What she did pass down, though, was the taste of that land.

And Borishali food, as my Sylheti-rooted mother will attest, isn’t just “East Bengali.” It is its own thing—subtle, distinct, and deeply personal. One dish that brings it all back is Amma’s Chingri Macher Pithe—a kind of shrimp cake, cooked on a tawa, and wrapped in banana leaves. Simple ingredients. Unmistakable flavour. A dish that acts like a bridge between a land lost and a home made. Between my Amma’s sprawling Borishal, my tiny 2BHK in Delhi’s Kalkaji.

| Prawns, cleaned and deveined | 250 grams |

|---|---|

| Fresh coconut, grated or chopped | 200 grams | 1 cup approx. |

| Green chillies | 3 pieces |

| Mustard oil | 3 tablespoons + for greasing |

| Turmeric powder | 1 teaspoon |

| Salt | 1 teaspoon |

| Banana leaves, washed | 2 |

Mixer Grinder or Sil Batta ; Flat Tawa; Lid to cover the tawa; Mixing Bowls

Begin by preparing all the ingredients. Clean and devein the prawns thoroughly, ensuring they are free of any shell or grit. Grate the fresh coconut or chop it finely if grating isn’t possible. Rinse the green chillies in water and trim off their stems.

In a mixer grinder, add the cleaned prawns, grated coconut, green chillies, and three tablespoons of mustard oil. Grind the mixture using short pulses until it is coarse in texture. The final mixture should not be smooth. If you are using a sil batta, grind the ingredients together using circular, even pressure until they come together as a coarse paste.

Once ground, transfer the mixture to a clean mixing bowl. Add one teaspoon of turmeric powder and one teaspoon of salt. Mix everything together thoroughly using your hands or a spoon, ensuring a homogeneous paste is formed.

![]()

Prepare the banana leaves by washing them well and patting them dry with a clean cloth. Cut the leaves into large circular or rectangular pieces—each piece should be large enough to hold a palm-sized portion of the mixture comfortably.

Grease one side of each banana leaf lightly with mustard oil to prevent sticking as well as to enhance the flavour during cooking.

Place half of the prawn-and-coconut mixture onto the greased side of one banana leaf. Using your fingers or the back of a spoon, flatten the mixture into a thick disc or cake that is about 1 to 1.5 centimetres thick. You can top this with a few thinly sliced green chillies if you prefer your food spicier.

Heat a flat tawa over low to medium heat. Once it is hot, gently place the prepared banana leaf with the mixture onto the tawa, ensuring the side with the filling faces up.

Cover the tawa with a lid to allow the steam to cook the mixture evenly. Cook for 15 minutes without lifting the lid too often. During this time, the bottom of the leaf will likely char and develop a smoky aroma—this is important to impart flavour and should not be mistaken for burning.

After 15 minutes, take the second banana leaf and place it over the exposed side of the mixture, forming a lid. Then, using a wide spatula or tongs, carefully flip the entire pithe so that the uncooked side of the mixture is now in contact with the tawa. Fold the edges of both banana leaves inward to seal the filling inside, creating a loose parcel. Cover again with a lid and continue cooking on low to medium heat for another 15 minutes.

Once the second side is cooked, turn off the heat and let the parcel sit for two to three minutes before unwrapping. This resting time helps the flavours settle and makes the pithe easier to cut.

Carefully open the banana leaves. The pithe should be firm to the touch and have visible char marks on both sides. Slice it into wedges or squares using a sharp knife.

Serve the pithe hot, either on its own or with steamed rice or a light pulao.

Priyanjali Datta is a Delhi-based marketing professional. You will find her at her best when experimenting in the kitchen, or when lazing around with her dog, Begum. She’s on Instagram as @pri_ekthappadfree

Priyanjali is also a member of The Locavore’s Local Food Club in Delhi. To become a member, sign up here.

You must be logged in to rate this recipe.