In the opening chapter of the book, author Indranee Ghosh writes about her grandfather’s culinary adventures in Cherrapunji, where he had moved to work as a preacher for the Brahmo Samaj.

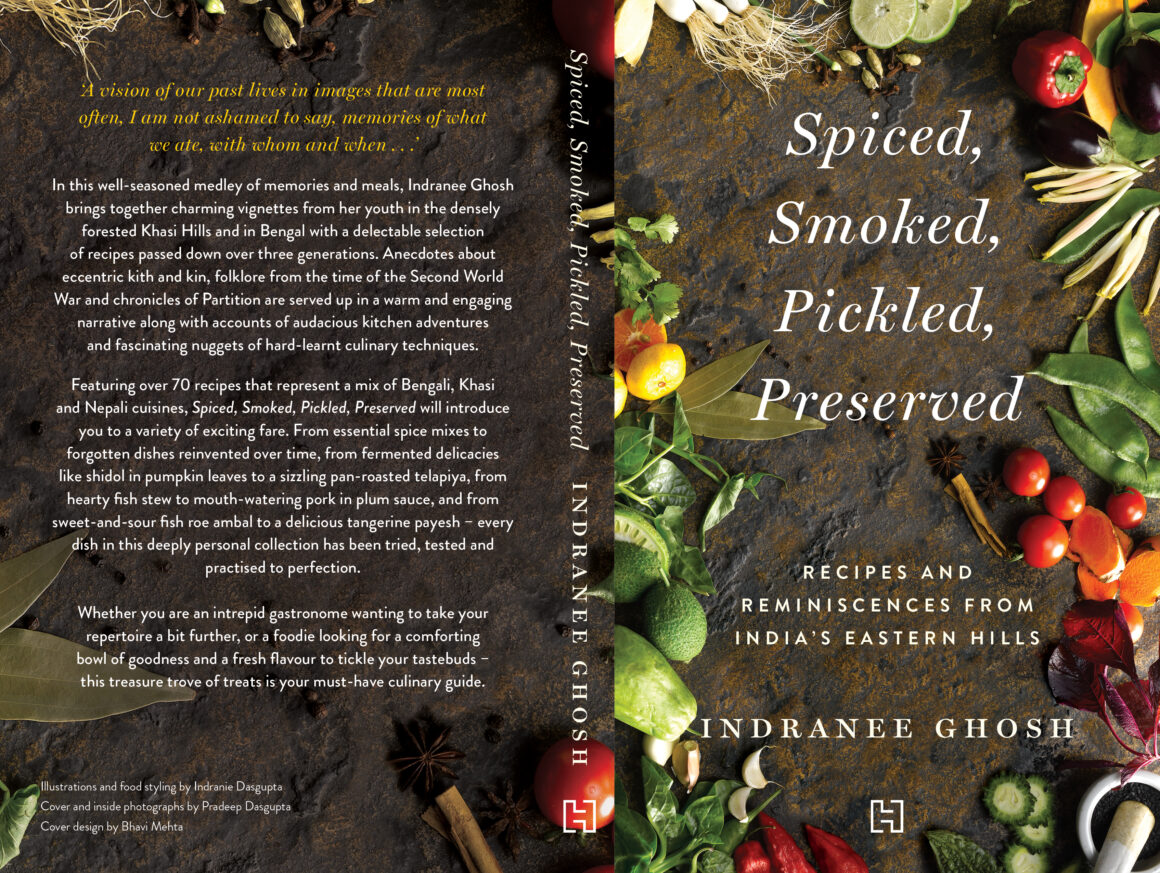

In Spiced, Smoked, Pickled, Preserved, the author brings together charming vignettes from her youth in the densely forested Khasi Hills and then in Bengal’s plains with a delectable selection of family recipes passed down over three generations to weave an utterly engaging narrative. Read this excerpt from the opening chapter:

A Doctor-Preacher in the Hills

Christian missionary activity in the Khasi and Jaintia hills began in the middle of the nineteenth century with the Welsh, Irish and Dutch. Later, there was the Ramkrishna Mission and the Brahmo Mission under the auspices of the Brahmo Samaj in Kolkata. The Brahmo Samaj grew to be a presence in the hills, particularly in Cherrapunji (now called Sohra), Laitkynsew and Shillong. The two Samaj houses in Shillong, one in Laban and the other in Police Bazar, were well attended. Brahmo hymns were translated into Khasi (by my grandfather), and they were sung at the morning services in Cherrapunji. The Samaj was also close to the Unitarian Church and each attended the other’s services on special occasions.

To start my story, in the early years of the last century, Binod Behari Roy, my maternal grandfather, left a promising career as a surgeon in Kolkata and went to the Khasi Hills to work as a preacher for the Brahmo Samaj. He first went to Shillong and then to Cherrapunji, where he lived for most of the year. My grandmother and the children moved to Shillong a few years after he had settled there.

There are two stories my mother always told me about my grandfather; one when she made semolina halwa for us at breakfast; the other when she made khichuri or pish-pash for lunch on rainy, or wintry days. With her expert mimicry, she would have me in splits. Let me tell you the semolina halwa story first.

There were two candidates for this post in the Brahmo Mission: one was my grandfather and the other was Nilmoni Chakraborty. The two were diametrically opposite, both in appearance and

character. A prominent Bengali writer has described Nilmoni Chakraborty in one of her books as the incarnation of her image of God: he was a slender man with a long, white, flowing beard, and hair curling at the neck. My grandfather was stocky, had straight black hair and a thick black moustache, hardly the image of God. He was fond of food (my mother said he was capable of eating a whole chicken or a whole leg of mutton), which was perhaps one of the reasons he had an enlarged heart, though walking up and down the hills might also have taken a toll. He died of a heart attack at 50 when my mother was about 14 years old, leaving my grandmother with four young children of her own and a host of foster ones.

As things turned out, it was Binod Roy who was selected to go to the Khasi Hills, much to Nilmoni Chakraborty’s chagrin.

Though life in the hills was difficult at first for my grandfather, he embraced the other joys of living in Cherrapunji. He gradually learnt how to cook and fend for himself, and found that the freshness of the vegetables, the fragrant rice, the purity of the ghee and the orange honey made any food taste good. In the beginning, however, there were mistakes, like when he attempted a semolina halwa, his usual breakfast with crunchy puffed rice, for a friend and himself. He mistook the honey for ghee and tried frying the semolina in it. It soon turned black and stuck to the ladle and wok, rising up in a sticky mess when he tried to lift the ladle. They threw away everything, wok, ladle, black mess, and ate puffed rice with honey and ghee that morning. This is how the halwa is normally made.

Find the recipe of the Semolina Halwa here.

There are two stories my mother always told me about my grandfather; one when she made semolina halwa for us at breakfast; the other when she made khichuri or pish-pash for lunch on rainy, or wintry days.

As I have mentioned before, my grandfather was fond of meat, of which there was a plentiful supply. But there was one phase in his life when he had to survive on very little, and this is my mother’s pish-pash and khichuri story.

The pristine surroundings of Cherrapunji attracted many visitors from Shillong. They came not only to discuss philosophy and religion but also to gossip about Brahmo Samaj politics. A favourite subject was Nilmoni Chakraborty. Not content with his situation, Chakraborty had sought to make things hard for my grandfather by trying to prove he was the more worthy candidate to spread the Word of God.

Once a year had passed after the Cherrapunji appointment, he decided to come in person ‘to see what Binod Roy [was] up to’. He came in the orange season when most harvesters went down to the annual village fair in Shella, which lay below Cherrapunji, to sell their oranges and buy livestock. My grandfather also went there, mainly to treat the sick with homeopathy, lance boils, remove thorns from callused feet and so on.

Nilmoni Chakraborty, on the other hand, went to deliver sermons. No one paid him any attention, and when he saw how people were flocking to my grandfather’s stall, he became even angrier, but there was little he could do. At the end of the day, when the market closed, and people trudged up the hills to their respective villages, Nilmoni Chakraborty was the only one being carried up on a coolie’s back.

At a distance, he saw my grandfather sitting on a rock to take a breather, and he shouted to his coolie, ‘Usko maro, woh chor hai! Hit him, he’s a thief!’ The coolie approached my grandfather threateningly with a stick in his hand, whereupon he got up and gave the coolie a gentle push. I can’t really vouch for how gentle that was, given his strength, for it sent both the coolie and Chakraborty (who popped out of the basket) rolling downhill till they reached the bottom. Neither was hurt since the hill was grassy. Nevertheless, Chakraborty filed a case against Binod Roy for wilful assault.

My grandfather’s defence lawyer was his friend and fellow Brahmo, Monmotho Das Gupta, who also owned a soap factory in Shillong. He advised him strongly against revealing that there was an actual push: He was to say that the coolie must have tripped and lost his footing. But my grandfather was adamant. Honest to a fault, he said, ‘I will neither lie in court nor in the eyes of God.’ So, when the court hearing commenced, he said, ‘Yes, I did push him, but under provocation. If he does it again, I will push him yet again.’ He was fined Rs 300, quite a sum in those days, and he paid it with his last penny.

He returned home expecting that he still had some money in the pocket of his kurta hanging from the bracket in his bedroom, but he found his dhoti and kurta, as well as his wallet, stolen in his absence. Yet, somehow, he made it back to Cherrapunji.

I don’t know what he did for food in that situation, although I don’t think he lacked basic stuff: most of his patients brought a little something from their farms in return for free treatment. ‘He lived on plain khichuri and pish-pash,’ my mother told me.

The pristine surroundings of Cherrapunji attracted many visitors from Shillong. They came not only to discuss philosophy and religion but also to gossip about Brahmo Samaj politics.

Pish-pash is a one-pot meal that is quick, easy, nutritious and delicious. Any meat may do for this, chicken, mutton mince or minced beef. You simply put the meat in a large pan with water, salt, bay leaves, onion, ginger, cinnamon, cloves and cardamom and set it to cook. Meanwhile, wash and soak the rice and chop the vegetables. When the meat has cooked for 10 minutes, put in the rice and vegetables. Let it cook on low heat for 20 minutes. If using a pressure cooker, cook for 10 minutes, and lower the heat after the first whistle. Then, serve hot with a generous dollop of butter or ghee with green chillies for those who want it.

As for khichuri, my grandfather had the commonest kind made with masoor dal (red lentils) and fine aromatic rice or red rice. This, again, is an easy one-pot meal. Tempering agents may differ for people, but the basic recipe is the same.

Find the recipe of the Masoor Dal Khichuri here.

This is an excerpt from ‘Spiced, Smoked, Pickled, Preserved: Recipes and Reminiscences From India’s Eastern Hills’ by Indranee Ghosh published in 2021 (Hachette India).