While women from certain communities in Goa are barred from the home and kitchen during menstruation, they are allowed to grind grains on the grinding stone. In this section of ‘Grinding Stories Retold: Songs from Goa’, Heta Pandit discovers how traditional gendered norms don’t quite apply to the grinding stone, and the responsibilities and rituals around it.

Heta Pandit—writer, researcher, and journalist—has been documenting the architectural history of Goa for over two decades. In her study of kaavi wall art in temples in Goa, she found that the stories they tell are also represented in another art form: the oral tradition of grinding songs, or songs sung by women as they dry grind grains, known as oviyos. These songs, just like kaavi art, are a reflection of Goan social history and structure, and its unwritten rules.

In learning from and documenting the custodians of these songs—women from the Maratha community in Sattari and Canacona, and the Christian Gavda community— Heta finds that grinding songs hold perceived acceptable social behaviour and in some ways, bring to light existing social structures. In 1684, the Christian Gavda community was banned from singing oviyos, specifically during pre-wedding ceremonies. Despite this ban, oviyos persist today, kept alive by the storytellers that have contributed to this book. Many of the oviyos shared have been composed by these storytellers, while others have been passed down orally by their family members.

The following two excerpts from the first chapter of the book, ‘A Prism View’, reveal how the act of grinding on a stone and singing around it embodies norms around women occupying space, within the household, and outside of it. The first excerpt offers insight into how and where grinding songs are performed and the rituals around them. The second excerpt features a song shared by one of the storytellers, Saraswati Dutta Sawant.

Saraswati, just like her peers mentioned in these excerpts—Lakshmi Vishnu Harvalkar, Amelia Dias, Louisiana Fernandes, Gloria Dias and Carminia Fernandes—is not only a contributor of this book, but also a keeper and creator of cultural knowledge in the form of these songs. Shubhada Chari is a teacher and researcher in Goa who helped connect Heta to the storytellers.

As we read these pieces, we learnt that the stone and songs make visible how social norms do not operate in broad strokes, but in specificities and with nuance.

Read an excerpt from the Grinding Stories Retold: Songs from Goa, published by Heritage Network.

Lakshmi Vishnu Harvalkar has never had a formal education and has had very little exposure to the outside world. Yet, she is very perceptive about the importance of preserving cultural content. Lakshmi Vishnu Harvalkar’s meetings and interviews were assisted by Anuja Naik Banaulikar of the Central Library, Goa that is currently under the purview of the Directorate of Art & Culture, Government of Goa.

On the occasions when Anuja Naik Banaulikar and I met Lakshmi, we were surprised by her responses and thoughtful answers to our questions. What was even more surprising was that neither she nor her husband showed any awkwardness when we touched upon the subject of menstrual segregation. Menstruating women or women in the perceived fertility age group of 12-50 are debarred from entering many temples and sacred spaces in Goa. Segregation for menstruating women is a traditional practice in Goa and also a taboo subject.

Segregation is almost always enforced and is rarely voluntary. A menstruating woman is compelled to occupy a corner of the angonn or courtyard. Often, she is made to share space with the cows in the cowshed. In some families, there is a special hut built for the members of the family during their menstruation periods. Mats for sleeping and eating vessels are either fumigated thoroughly or burnt at the end of the isolation period. The special hut is not used for any other purpose. The clothes the women wear during this period are also either fumigated or destroyed. Menstruation is not discussed by the other members of the family, including the menstruating women themselves. The period is obliquely referred to as when “the crow bites you” or when “you have to sit outside” or “stay away”.

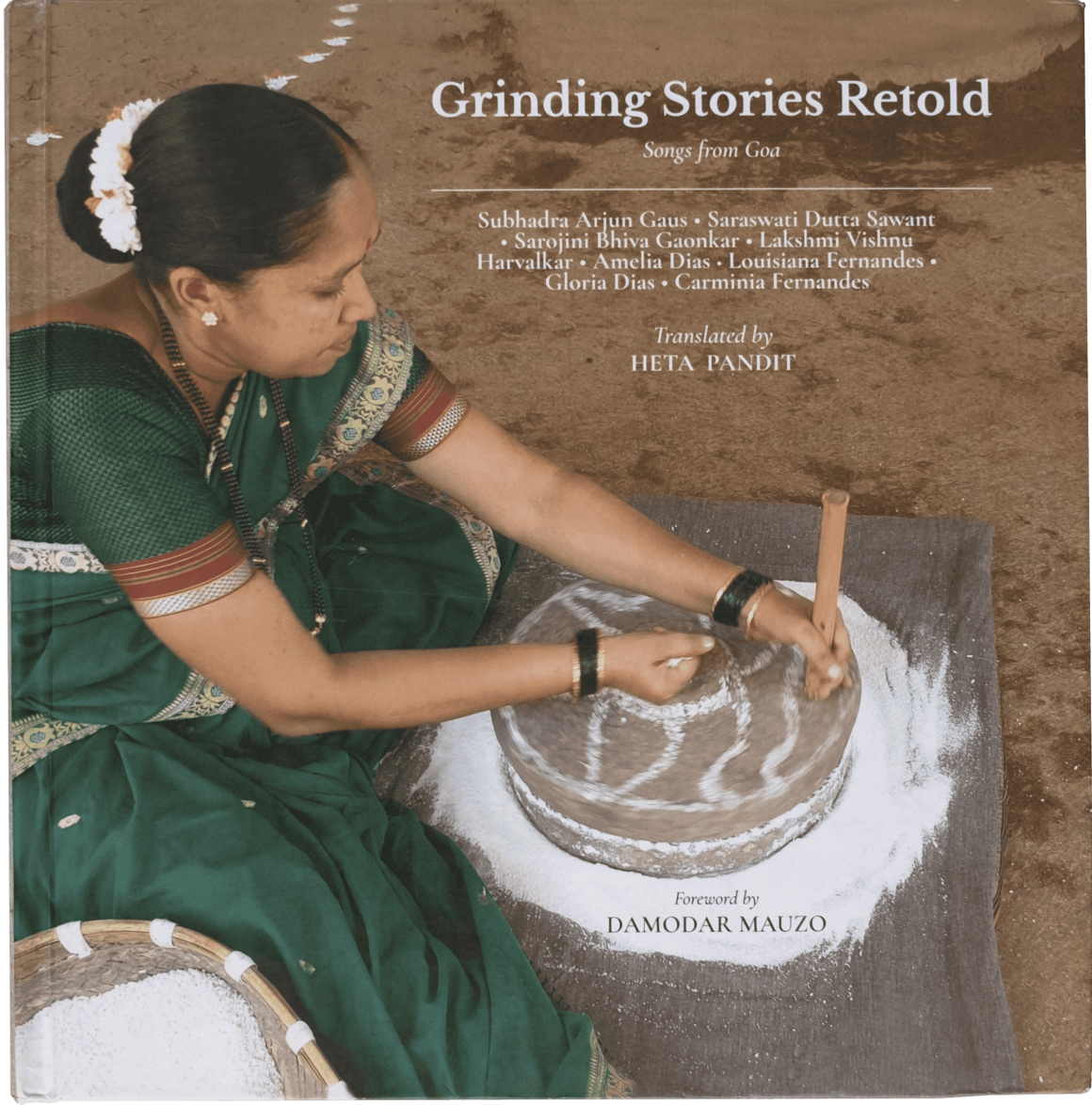

Menstruating women cannot enter the kitchen or other parts of the house especially where the family deities are kept for worship. They are forbidden from touching any cooking pots or vessels. They are also forbidden from coming into physical contact with any other member of the family, including children. What is interesting, however, is that they are allowed to touch the grinding stone. The grinding stone has a wooden handle that helps turn the stone. A woven mat is spread on the courtyard floor and a stone or metal mallet is used to hammer the handle in when it comes loose during use. The floor mat is sometimes replaced with an old sari and, in some homes, a sheet of plastic tarpaulin.

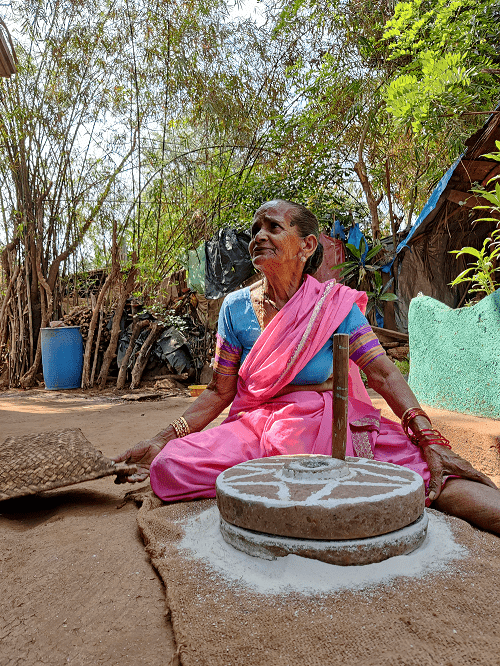

A menstruating woman is allowed to spread the mat, sit at the grinding stone, hold the handle and grind. There are, however, certain restrictions. She can only hold the handle at the top of its shaft. Her posture while working on the grinding stone is also different when she is menstruating. The normal posture involves the stretching of the one leg right out and the other leg folded in. This position is referred to as phatkal and is strictly mandatory whilst grinding.

In the menstruating period, however, and while grinding, a woman is required to fold the stretched-out leg with a bended knee. She is allowed to handle the grain. She can scoop the grain with a free hand and feed it into the well of the grinding stone. However, she cannot touch the flour that spills out of the folds of the stone. “The flour must be collected by someone else.” This is because the grain is considered “virgin” before it is milled. Normally, men do not handle the stone except perhaps to lift it and place it on the mat if necessary. When a wife, mother or daughter-in-law is menstruating the men in the household will collect the flour from the mat, clean the stone after collection and put it away.

By and large, the handling of the stone and the process of grinding or milling is in the female domain. And though both male and female children of the household gather around the stone while at play, the boys in the house are never encouraged to try their hand at grinding grain.

A menstruating woman is allowed to spread the mat, sit at the grinding stone, hold the handle and grind.

The other grinding stone set in the house, the rogdo and vhaan, is used for wet grinding. It also falls exclusively in the female domain. Yet, one neither sings at this wet grinding stone nor does it ever double up as a percussion instrument. The third grinding stone, the faator, a flat stone with a lozenge-shaped hammer is used for wet masala grinding. No singing takes place while working this either. However, a wooden trough used for kneading dough, called the dhavllyo, is often used as a musical instrument. Two wooden ladles with coconut shell cups are used to scratch the surface to make a rhythmic scratching sound while singing. There is also a large wooden mortar and wooden pestle called the mussal. This is used for pounding dry condiments such as red chillies or turmeric into dry masala.

The only community in Goa that sings and dances to the sound of the mussal is the Christian Kshatriya community of the village of Chandor (formerly Chandrapur) in South Goa. This song and dance routine, called the mussal khel, is traditionally performed annually by the men of this village with one single female performer. Sometimes, a male performer performs the female role dressed in a red sari. It is believed that if the dance is not performed, the village of Chandor would suffer unprecedented misery.

No such fear hangs over the singing of the oviyos. Once contacted, the storytellers were isolated from the rest of the village and asked to sing the songs they knew from memory. No written questionnaire was prepared. The storytellers are familiar with the mobile phone but uncomfortable with notes being made in pen and ink. As they sang, Shubhada roughly gave the gist of the story and I wrote, in English, the story as I understood it in its first flush, rewriting it in verse later.

There are two anecdotes worth mentioning here. Once, when I asked storyteller Saraswati Dutta Sawant to repeat a few lines that she had just sung, she asked if my mobile phone had “no recording device?” What is interesting is that the storyteller herself does not possess a mobile phone. She has never used one. The other anecdote involves her counter interviewing Shubhada and me with reference to the purpose of this collection. “Will you be doing a book? A film?” she asked. She also insisted that we give her a copy of any future publications. Saraswati has never learnt to read.

All the storytellers have travelled on performing tours under various programmes of the Directorate of Art & Culture, Government of Goa. They are aware of the importance of generating awareness on Goa’s intangible cultural heritage. They have a repertoire of songs in their treasure troves and know exactly what stories you are looking for when provided with a cue. There are songs sung for the monsoons, for the harvest, for weddings, for births, for the ceremony congratulating a woman on her pregnancy after she crosses the eighth month or third trimester, for battles won and lost, of widowhood.

Meeting Christian Gavda community members Amelia Dias, Louisiana Fernandes, Gloria Dias and Carminia Fernandes in their village of Paroda, Quepem taluka, South Goa district gave us some interesting insights into the genre of oviyos. The 1684 ban on singing in the native Konkani did not seem to have affected the singing of oviyos at Christian Gavda weddings.

Two or more women sit at the grinding stone and sing. There are no restrictions on widows, unmarried women or young girls singing. There are no restrictions on menstruating women singing and sometimes, “if we are tired, the men in the house also help us grind the grain”. The grinding stone is often purchased at the market and not handed down from mother to daughter. The stone is the centre focus of all wedding songs and yet is never decorated with flowers, rice paste or turmeric and vermillion.

On the other hand, for a Hindu wedding, it would be customary to decorate the stone with vermillion, flowers, turmeric and rice paste before the songs begin. The Christian community uses a functioning grinding stone while the Hindu community has nowadays resorted to using a smaller version of the grinding stone.

Wedding songs have also been truncated and the whole ceremony has become an act

of tokenism.

There are songs sung for the monsoons, for the harvest, for weddings, for births, for the ceremony congratulating a woman on her pregnancy after she crosses the eighth month or third trimester, for battles won and lost, of widowhood."

Despite the ban and disapproval, Catholics in Goa continued both these traditions “through the back door”. In the story titled My Grinding Stone is Made of Gold, My Mat Made of Silver, the storyteller addresses the two main goddesses of the village and says, in translation:

“O Mother Sateri! O Mother Pavnai!

My grinding stone today is made of gold

The mat I sit on is made of silver

All the goddesses have come down flying over the

wedding canopy.

Come to the ceremony all you

Married ladies of the village of the towns and of

the territory turmeric and vermillion await you.

Place the ceremonial grinding stone

Carefully for the grinding stone is life.”

In this song, there is one line that reflects the social status of a married woman in a Goan village. “Come to the ceremony all you/Married ladies of the village/Of the towns and of the territory/Turmeric and vermillion await you.” The song is significant in both its content and intent.

This is an excerpt from ‘Grinding Stories Retold: Songs from Goa’ published in 2023 (The Heritage Network).

Heta Pandit’s first “real job” was with famed ethologist Dr Jane Goodall on a chimpanzee research station in Tanzania, East Africa. Since then, she has written 11 books on Goan heritage, and is currently working on a book titled Objects and Memories from Goa. A Homi Bhabha Fellow and a founder member of the Goa Heritage Action, she lives in Saligão, Goa with her dogs Goru and Potyo.