This recipe has been excerpted from Silent Cuisines: The Unsung & Disappearing Foodways of Gujarat’s Adivasis by Sheetal Bhatt, a cookbook documenting some of the culinary traditions of tribes from the foothills of the Aravalli mountains of Gujarat, across six northeastern districts of the state.

Silent Cuisines first began as an attempt to document Gujarat’s folk rice varieties, kept alive by custodian Adivasi communities. With Aranya, a Farmer Producer Organisation run by small and marginal Adivasi farmers from the forests of the Aravalli hills, and Paulomee Mistry, director of Aranya, Sheetal was able to access regions where certain traditional varieties were still grown and eaten. However, as they spent time in the thick forests and dense vegetation of the region, it became apparent that rice was only one part of a diverse foodscape of pulses, grains, and native wild greens that were still grown in these unspoiled lands and eaten by the Garasia, Dungri Garasia, and Bhil communities in the region.

The recipes in this book, of which the Bhaat Nu Osaman is one, cover what is eaten across all seasons in districts of northeast Gujarat—specifically the districts of Banaskantha, Sabarkantha, Aravalli, Mahisagar, Dahod, and Panchmahal. As community elders express concern over these disappearing foodways, with government schemes and younger generations’ tastes prioritising more commercial or popular foods, this documentation is an attempt to preserve the tastes and flavours of a region, and offer it the tools of aspiration—beautiful photos and publication—that could contribute to keeping them alive.

The fertile hills of Dahod and Panchmahal have long supported extensive rice cultivation, providing the Adivasi communities with a rich variety of fragrant, glutinous, and nourishing desi (native) rice. These traditional rice types, with their diverse colours, shapes, and growing cycles, were once considered as family heirlooms. However, the rise of high-yield crops following the Green Revolution has led many farmers to abandon these cherished varieties.

While working on this book, I met middle-aged Adivasis who fondly recalled the mithash (natural sweetness) of rice from their youth. “When we cooked Khetrad, Raatadiyu, Doodh Kamod, or Gaduli (names of native rices), the whole house and street would fill with their aroma,” Sanabhai reminisced. “Desi rice made the most wonderful ohan or bhaat nu osaman. We’d eagerly wait for Maa to skim some ohan for us. Her favourite child got the biggest share, but even a little ohan was enough to keep us energised and happy for hours. It wasn’t just the taste—it was the smell that satisfied us most.”

When I asked how often he drinks ohan now, Sanabhai sighed, “Rarely. We don’t grow desi rice like before. Many of our seeds are lost. The rice from the PDS store or hybrid crops smells terrible, and the ohan it makes is thin and watery. No one likes it anymore.”

‘Osaman’ comes from ‘osavu’—a Gujarati verb meaning ‘to strain cooking liquid’. Traditionally, in Indian cuisine, the leftover cooking liquid from rice, dal, and pulses is valued for its nutrition. In Gujarati cuisine, osaman from lentils is tempered into a rasam-like dal, while bhaat nu osaman (rice osaman) is sipped as an energy-boosting drink, often given to those recovering from illness.

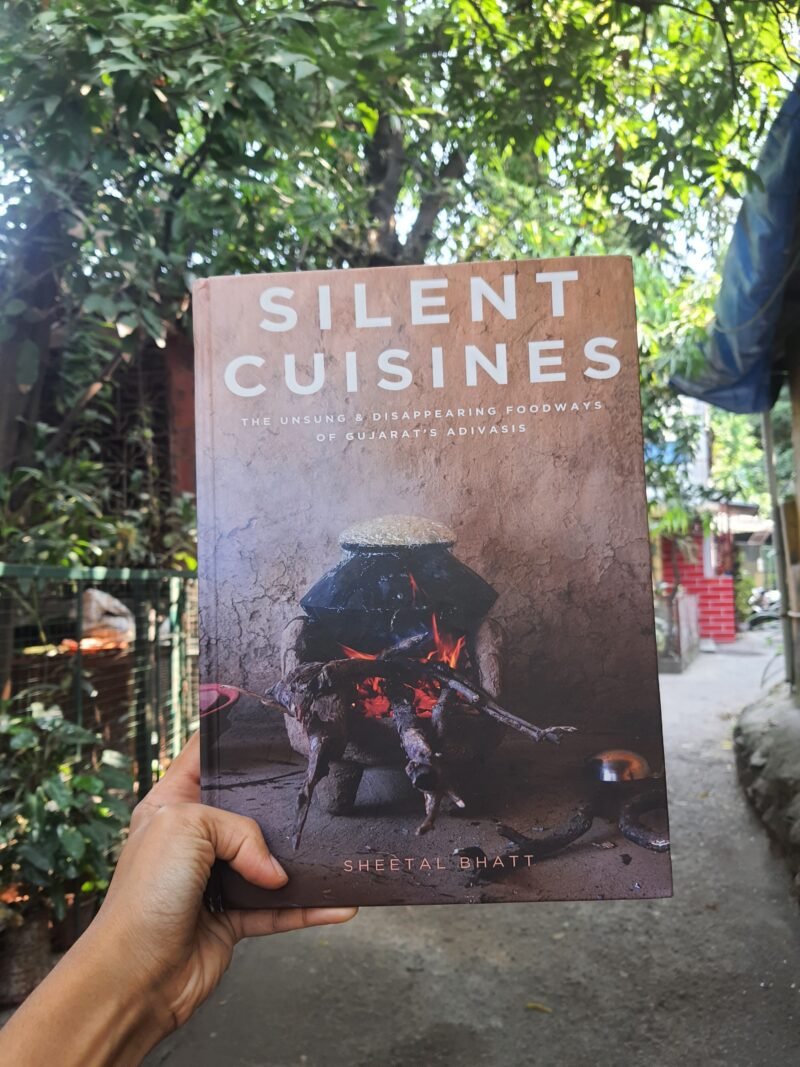

Native rice varieties make the most wonderful Bhaat Nu Osaman, according to Sanabhai, an Adivasi community member Sheetal spoke to. Photo by Sheetal Bhatt.

Silent Cuisines, a project of Disha, authored and photographed by Sheetal Bhatt.

| Red rice | ½ cup |

|---|---|

| Water | 5-6 cups |

| Salt | to taste |

What You Will Need

Claypot or heavy-bottomed saucepan; bowl; strainer/ colander

Instructions

Place the rice in a bowl and rinse it under running water 2-3 times until the water runs clear.

Add fresh water and soak the rice for 30 minutes.

In a large saucepan or a clay pot, bring the water to a gentle boil over medium heat.

Drain the soaked rice and add it to the hot water. Add salt to taste and stir once to prevent sticking.

Reduce the flame to low and cook the rice uncovered. Check for doneness by pressing a grain of rice between your fingers—it should be soft but still hold its shape.

Once the rice is cooked, place a bowl under a strainer or colander.

Pour the contents of the pot through the strainer. The liquid that collects in the bowl is the osaman.

Bhaat nu Osaman is best served warm, sipped like a light broth.

Sheetal Bhatt is a social development professional by training and has worked extensively with marginalised communities in Gujarat. Her journey into the study of food and hyper-local regional Gujarati cuisines began a decade ago with her website, www.Theroute2roots.com.

You can find more recipes and their stories from Silent Cuisines here and here.

You must be logged in to rate this recipe.

Sign in with email